“Locky” Crypto-Ransomware Uses Malicious Word Document Macros

Several security researchers have discovered a new type of malware that jumps onto the ransomware bandwagon, encrypting victims’ files and then demanding a payment of half a bitcoin for the key. Named “Locky,” the malware depends on a rather low-tech installation method to take root in a user’s system: it arrives courtesy of a malicious macro in a Word document.

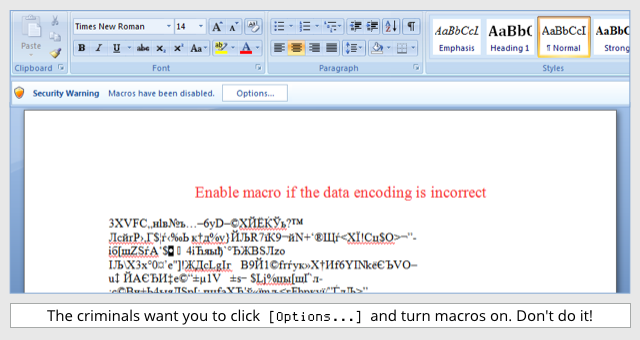

Security researchers Kevin Beaumont and Lawrence Abrams each wrote an analysis of Locky on Tuesday, detailing how it installs itself and its components. The carrier document arrives in an e-mail that claims to be delivering an invoice (with a subject line that includes an apparently random invoice number starting with the letter J). When the document is opened, if Office macros are turned on in Word, then the malware installation begins. If not, the victim sees blocks of garbled text in the Word document below the text, “Enable macro if the data encoding is incorrect”—and then infects the system if the user follows that instruction.

Somehow, this malware has already infected hundreds of computers in Europe, Russia, the US, Pakistan, and Mali. The malicious script downloads Locky’s malware executable file from a Web server and stores it in the “Temp” folder associated with the active user account. Once installed, it starts scanning for attached drives (including networked drives) and encrypts document, music, video, image, archive, database, and Web application-related files. Networked drives don’t need to be actively mapped to be found, however.

“When Locky encrypts a file it will rename the file to the format [unique_id][identifier].locky,” wrote Abrams. “So when test.jpg is encrypted it would be renamed to something like F67091F1D24A922B1A7FC27E19A9D9BC.locky. The unique ID and other information will also be embedded into the end of the encrypted file.”

Locky’s mechanics are pretty much like every other ransomware package currently floating around in malware marketplaces. It leaves a ransom note text file called “_Locky_recover_instructions.txt” in each directory that’s been encrypted, pointing to servers on the Tor anonymizing network (both via Tor directly and through Internet relays) where the victim can make payment, and changes the Windows background image to a graphic version of the same message. It also stores some of the data in the Windows Registry file under HKCUSoftwareLocky.

Since yesterday, Locky has been picked up by most of the major malware scanners. But given that the malware depends on would-be victims using older versions of Microsoft Office or falling for some of the most preposterous social engineering ever, the most likely targets of Locky are probably not updating their anti-virus software—if they have any.

Stu Sjouwerman, the CEO of security awareness training company KnowBe4, pointed out that those targets may be legion. “The old Office macros from the nineties have not gone away and the bad guys are combining this old technology with clever social engineering,” he said. “If you trust antivirus software and your users not clicking ‘Enable macros’ you are going to have a problem. You can’t just disable all macros across the whole company because a lot of legacy code relies on macros. Telling all users to sign their macros will also take months.”